- Resource Center

- Professional Development

- Articles & Videos

- How Sanctions Work – A Crash Course in Compliance

1 March 2022

| by Globalization and Localization Association

How Sanctions Work – A Crash Course in Compliance

Sanctions against “rogue regimes” are not new. But in the last 30 or so years, the “rogue regimes” were rather marginal from the economic point of view. This time, the sanctions target Russia, one of the greatest powers of the world, which was, until now, integrated into the world economy in countless ways

Sanctions are not like a government says something and then it’s done. No: in a democratic system, a government depends on private businesses to enforce them. The cynical take on this is that the government assumes all the authority, while the responsibility is pushed to private, often small, enterprises

Sanctions can take a number of forms, just to name a few: travel bans, confiscation or freezing of assets, limiting or barring access to international financing or infrastructure (like disconnecting major Russian banks from SWIFT, underway at the time of writing), and—what is most relevant for us small businesses—bans or restrictions on trading and exports.

Some of us still remember what it is like to live in a country under an embargo. In the 80s, the USA and its allies maintained a set of bans called COCOM against the so-called Comecon countries (the Soviet Union and its allies). This effectively banned the export of any advanced technology, including all computing devices based on microprocessors, to these countries. The fact that I had occasional access to a genuine IBM PC XT in Budapest in 1985 was a result of illegal import—smuggling, to be precise (disclaimer: I didn’t do the smuggling, I was 14 at the time).

A little later, our countries moved (or were moved) to the luckier side of the embargo. Also, most small businesses did not really have to deal with the restrictions. Exporting goods was an expensive operation, usually requiring a larger organization: plus, it was not customary to export pretty much anything to the countries on the list back then.

In 2022, however, everyone who offers an online service is practically exporting services—to every country the service is accessible from. For example, my company develops business software and sells it online, both in the form of subscribed cloud services (or software-as-a-service, SaaS) and traditional licenses. The moment a Russian organization with Internet access signs up for it, we are exporting intellectual property and/or services to Russia. This can even happen without our prior knowledge or permission.

By default, businesses must watch and comply with all laws and regulations that apply to them. Export regulations are no exception. When there is a new regulation that bans or restricts trade with certain countries or organizations, it’s our job to check if the restriction applies to our products or services (and if it applies to all of them or just to some), and to our existing or prospective customers in the area (if not all).

If a business is based in the EU, it must first and foremost comply with EU export restrictions. Authorities and agencies in your country may also provide more guidance, but as a rule, the EU follows a unified policy when it comes to foreign trade. Outside Europe, your country's trade or export authority is the place to check for guidance.

This might not be enough, though. If, for example, as a European business, you export to the US, you probably need to watch US export regulations, too, because it might be a prerequisite when you sell to certain organizations. The same applies to other countries.

In the EU, I recommend that you watch two sources: The information website of the Council of the European Union or the European Commission to learn about the principles, and the EU sanctions map to find out which territories are under sanctions, and what trade is restricted or banned.

For example, if you want to check the currently effective sanctions against Russian entities and individuals, click Russia on the map, and then click Info in the little window that appears. This will take you to a detailed website. You can view lists of organizations and people under restriction and also the affected products or services.

If you export software or online services, they may, under EU or USA export regulations, be categorized as “Dual-use goods”. In principle, this includes all products and services that are suitable for military use. However, to find out if your product really belongs in this category, you need to check the definition. This link shows how the EU categorizes dual-use goods. The way I read this definition, a common translation management system that might be relevant in this community, is not a dual-use product. However, if you have doubts, be sure to consult your legal counsel.

It is also a question whether you must stop existing services, or you simply must not engage in new contracts. For that, it’s worth reading the directive or regulation—in the Sanction map, click the Legal acts title at the top and scroll down for a list of legal regulations.

In the USA, you need to look for the so-called Consolidated Screening List. This lists all the countries and entities that fall under any restrictions. This is available on the U.S. International Trade Administration (ITA) website. Use the form to look up countries and entities.

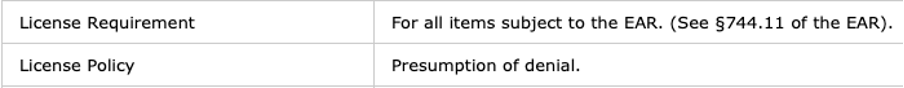

Once you find your target entity, you will get a data sheet that will refer to the Export Administration Regulations (EAR). The most interesting items are the License Requirement and License Presumption:

The License Requirement may only refer to certain products or product groups (in the example, it isn’t the case). If it does, you need to find out if it applies to your product. To do that, head over to the EAR website of the U.S. Dept of Commerce for the Commerce Control List. If you export software—no matter whether it’s SaaS or licenses—, your code will start with 4D.

If you are exporting products and services from the USA, you need to be intimately familiar with this. For European businesses, compliance with this may be required if they want to export to the United States. Outside these regions, check with your national trade or export authority.

Some companies go beyond what is required by law—for example, Apple stopped selling iPhones in Russia and MasterCard won’t allow payments to be made to or from Russian cards or accounts. (Again, the cynical take on this is, of course, that they do this because payments from Russia will become all but impossible in the next few weeks.) As a business, it is up to you to restrict your business more than required. However, make sure this does not get you into legal trouble—because a legal agreement, in the absence of government sanctions, remain in place. And remember that the reality for small businesses is quite different than large ones.

The best you can do is keep your eyes open because you may not be able to anticipate the restrictions. Our governments usually act on privileged or classified information that they do not share with businesses or individuals at large. I’m not saying this is right—but acting on righteous anger may end up damaging your business without really helping anyone. Once the sanctions are in place, though—you must implement them immediately: and I hope this article will help you prepare.